A few days ago, we witnessed the largest ever ransomware attack, which impacted over 230,000 individual computers across 150 countries. Cybercriminals exploited known vulnerabilities in the Windows OS and compromised the human element to deliver the malware payload as an email attachment. The virus known as Wanna Decryptor (a.k.a. WannaCry) was used to encrypt data on the compromised hard drive, and spread like a wild fire across the network.

The vulnerability primarily comes down to a network file sharing protocol called Server Message Block (SMB). It is the mechanism whereby Windows shares files and communicates information around the network about serial ports, printers and so on. It also communicates with servers that are configured to receive SMB requests. Switching it off permanently is not an option but temporarily disabling it is fine for troubleshooting. This Microsoft Knowledgebase article explains how to do it. Also involved was NBT (aka NetBT or NetBIOS over TCP/IP) that permits older devices still using the NetBios API from the 1980s to hook up to modern networks.

Screenshot: Microsoft

The worm leveraged the flaw to utilize out of date (unpatched) SMB/NBT versions to spread itself throughout a network and replicate. Microsoft stated “Remote code execution vulnerabilities exist in the way that the Microsoft Server Message Block 1.0 (SMBv1) server handles certain requests. An attacker who successfully exploited the vulnerabilities could gain the ability to execute code on the target server. To exploit the vulnerability, in most situations, an unauthenticated attacker could send a specially crafted packet to a targeted SMBv1 server.”

When did Microsoft know about it and what did they do?

Microsoft awareness occurred on the same day as the rest of the world, when the ShadowBrokers hacker group dumped part of the NSA’s arsenal of hacking tools in public view. The NSA had weaponized that exploit by building code around it. The resulting artefact was codenamed Eternal Blue.

Microsoft set about developing a patch for affected operating systems and made it available free of charge on March 14 2017. The relevant Microsoft Security Bulletin MS17-010 details all of the systems that were impacted, which is most of them, including MS Server.

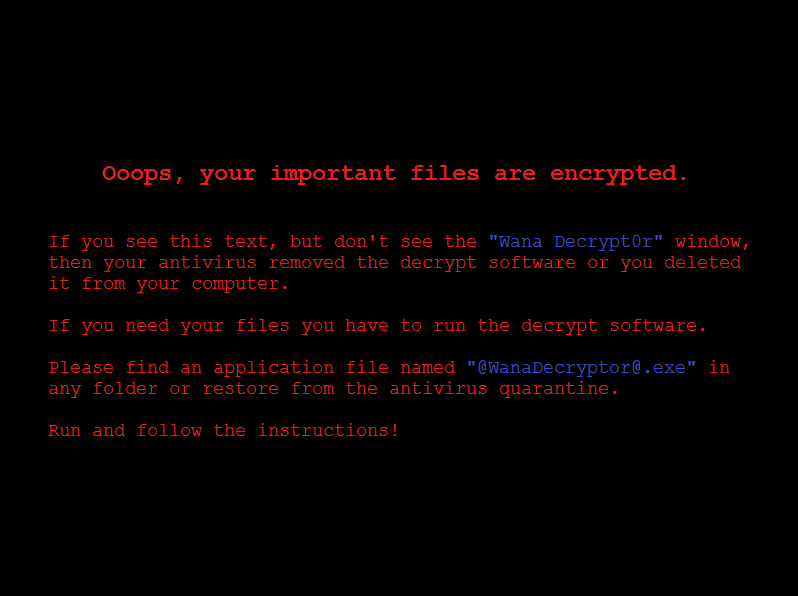

Once compromised, the victim computer screen is locked with a message demanding $300 ransom to be paid within a few hours via Bitcoin. Once that timeline expires, the ransom increases to $600 and even $1200. Even after paying up, you’re not guaranteed to remain secure from future attacks by the same malware payload.

Victimizing Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies

The role of Bitcoin is particularly important in the entire saga. Back in the day, prior to the age of cryptocurrency, cyber criminals demanded ransom to be paid via credit cards. Since credit card transactions are traceable, cyber criminals would usually end up getting caught or be very careful demanding ransom from victims. As a result, a large-scale ransomware attack that compromised thousands of systems across over hundred countries never took place.

In the age of Bitcoin, where all cryptocurrency transactions are virtually untraceable, even the most amateur cyber criminals are free to exploit known vulnerabilities and demand ransom from anyone they want – even government-run hospitals.

All of this means that Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies in general are a victim to the cyber crime underworld. These payment methods have emerged as a safe haven to hackers, and governments around the world are looking for ways to make cryptocurrencies traceable – an objective that clashes against the very philosophy of cryptocurrency.

Which Windows OS Are at Risk?

The vulnerability exists in older, unsupported versions of the Windows OS. Examples include Windows XP, Windows 7, Windows 2003 Server and Windows 2008 Server. Microsoft has recently released the patch with the title MS17-010. Windows users are expected to apply the patch on Windows Vista, Windows Server 2008, Windows 7, Windows Server 2008 R2, Windows 8.1, Windows Server 2012, Windows 10, Windows Server 2012 R2, Windows Server 2016.

If your older Windows OS doesn’t has the patch installed, the ransomware could target your computer.

Globalization

The malware targets many non-english speaking regions as well. The malware software has been translated into Bulgarian, Chinese (simplified), Chinese (traditional), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Filipino, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Vietnamese.

How the spread of the infection was interrupted

The UK security analyst known as Malware Tech on Twitter quickly saw that the code was attempting to access an unregistered domain iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea[dot]com and immediately registered it. This is part of his job role, as he explains on his blog post that describes the event How To Accidentally Stop A Global Cyber Attack. That domain then became a sinkhole to help track the spread of the virus thus far. The code logic was simple – if the malware successfully contacted that domain, then it stopped executing. A so-called Kill Switch. However, According to the latest report from McAfee, there are variants of this malware in the wild that do not require checking through the kill-switch or exploiting NetBIOS. As such, these variants would be executed in all cases.

What next for this particular ransomware weapon?

The attack that started on Friday May 12 spread with such wildfire speed that it could have wreaked havoc were it not for the accidental interruption. It is logical to assume that a repeat attack will quickly follow with the kill switch removed. While the world has woken up to the need to apply the Microsoft update (patch), not everybody will be able to do that. The only surprise is that this expected follow-on attack has not already occurred at time of writing.

Success with the WannaCry worm means that cyber criminals will likely develop several alternate versions of the virus to exploit the same Windows vulnerability. And assuming that many Windows users will continue to run unpatched or unsupported versions of the OS, cyber criminals will likely see more success with their malicious efforts.

Protection against the WannaCrypt attack

Microsoft recommends the following:

- Install the security update MS17-010

Other options include:

- Disable SMBv1 with the steps documented at Microsoft Knowledge Base Article 2696547 and as recommended previously

- Consider adding a rule on your router or firewall to block incoming SMB traffic on port 445

- Windows Defender Antivirus detects this threat as Ransom:Win32/WannaCrypt as of the 1.243.297.0 update.

Lessons for Internet users

Every security breach or hacking attack that makes the headlines also delivers at least one significant lesson for Internet users. Often it is the importance of maintaining a sensible password security program (and not using the same password for every account, for example). Ransomware attacks that encrypt the data on a system usually have few successful outcome options. Paying the ransom is no guarantee that data will be properly restored. It may not be possible to simply ignore the data loss and carry on regardless. The best solution is to restore from an offline data backup that is backed up religiously with appropriate regularity. Backing up to Amazon or DropBox, for example, is not enough. These appear merely as folders in a user’s system and can be encrypted just like the hard drive.

The world’s biggest ever ransomware cyber attack from Friday seems to have abated. But has it really? How exactly did that malware work? What vulnerability did it exploit, and how? What do we expect next and can you protect against similar attacks?

It’s time to take external data backups seriously.